- Home

- Reema Rajbanshi

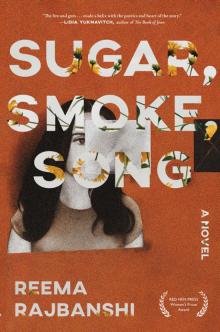

Sugar, Smoke, Song Page 7

Sugar, Smoke, Song Read online

Page 7

“Baby,” I begin, and twirl his curls with my finger. But he hunches as if dreading what I might say, and studies the fifteen male torsos bobbing together.

So I pace the stairs with my flashlight and watch other city-dwellers do their dirty deeds. Row E, Korean guy feels his white girlfriend’s ass; Row D, two bald black men curl and uncurl their hands and cry; Row B, Dominican girl hugs man on the left, man on the right, stroking each one’s cheek. I’m her—the hussy, the tomato in a sandwich, a woman who can’t choose between her men, even when one’s gone, and the other’s getting ready to go.

Act III now, when the black swan flits dangerously into the ball. The Prince, thinking her the enchanted swan princess, draws close to dance. The tempo picks up, the black swan does piqué turn after turn about the Prince, and I run the stairs back to Sammy before it’s too late.

“I still love you,” I say, just as the Prince embraces the black swan as his wife.

I might as well be telling a ghost, ’cause Sammy stares awhile at the stage, then looks at me with I’m-sorry-but-I’m-lost-to-you eyes.

“Don’t you love me?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” he says, “how I feel.”

“I don’t know,” Walt had said. “‘Life’s a poor player,’” Shakespeare wrote, “‘that struts and frets his hour upon the stage.’” Rehearsal goes something like this, I think. You do the same moves over and over, hoping for the moment—voila!—when you get the dance right. Except, fuck-up that I am, I haven’t. I haven’t yet.

“I’ll make changes,” I say. “I promise.”

Sammy frowns at the Prince as if his pirouettes en pointe are to blame.

“Okay, okay. Don’t say anything,” I say. “We’ll talk about this later. We’ll take it one day at a time.”

“All right,” he says, and because it’s intermezzo, the lights go out.

Revelation Moves Like That. For fifteen, it’s just me and the understudy blinking at the shadowy stage, when I know Sammy’s been spelling the truth. I’ve watched this knobby-legged waif, perched in the orchestra seat, in her Odile variations: the black swan who comes to devastate the party. Her reckless lines, her impossible toes, yet a cold reach in how she will throw back her head, fling up her foot as she claims what every partygoer assumes is Odette’s. I don’t know her real name but what is real in the theater anyways? When is black white and white black and where can you claim your love so street-goers won’t spit, and how did I, learning to count in Spanish for this slum dance, think I could match of all things a black-and-white swan ballet?

We walk the long way back to Sammy’s, along the Hudson, its waters dark and flat like they could be Swan Lake. We walk without touching, side by side, paces matched at last, and I tell Sammy the other ways the story ends.

“Russian and Chinese ballets kill off the sorcerer,” I say. “That way, the swan princess becomes human and marries the prince.”

“A Hollywood ending,” Sammy says. “Impossibly happy.”

“In one version,” I say, “the swan princess kills herself. The prince jumps after her into the lake.”

“That’s even worse,” Sammy says. “A Bollywood ending. Too melodramatic.”

“In another version,” I say, “the prince asks for her forgiveness. But the swan princess dies in his arms, and the lake takes them both.”

“Why should they die?” Sammy says. “They both made honest mistakes.”

I don’t know. I don’t know anymore, between Sammy and me, me and Walt, between us three, who’s the prince, the black swan, the swan princess.

Drumroll please.

“I liked tonight’s ending,” Sammy says. “She stays a swan, he stays a prince, and they part. Sad but real. A modern love story.”

And there I have it.

THE STARS OF

BOLLYWOOD HOUSE

Raw Kordoi, Salted

2carambola

1teaspoon salt

1teaspoon chaat mix

1.Wash and slice carambola into stars.

2.Season with chaat and salt to taste.

3.Mix in by hand. Enjoy.

BHUPEN

I blame that stupid boy. I could always smell a fish in a suit, even one sidling on bare bamboo legs into the restaurant. All us men paused with our knives to look. Punjabi, Massachussetts, law, he said in one unsure breath. I should’ve told her—untried hands, trembling lips—half-cooked meat should always be sent back to the kitchen. But she sat between us, before the drunk face of Meena Kumari, and said, “Baba, he’s heard all about our Assam tea.” So I slipped off to the kitchen, where the men hummed wedding tunes, and I added extra chilies to the momos, the pakoras, the pithas I laid before him. Burn, you capitalist son of a babu, I smiled, if you end this badly.

Though what good is it to rewind? If I were left with an old man, I too would weep. I too would shuffle through a Jersey studio, shrinking—130 to 98—into Bollywood movies. Every evening, I bring sour tomato-and-lime tenga all children love; New Year’s pithas handrolled with sugared sesame; bitter eggplant roasted and mashed with cilantro and salt. But every evening, Jumi turns to the screen: doe-eyed Nutan wailing to the moon, tipsy Meena dancing on broken glass, the hunched shoulders of long-faced Nargis. Every midnight, she rises and roams, trailing starfruit on the concrete. The one food she touches flares in the dark.

When Jumi first left, I looped Lawrenceville two hours before finding stars that led to her theater lot. She crouched on the curb, staring at a dead deer, their tawny forms draped along the sidewalk. Except the deer’s smashed skull fell over the curb, its antlers an upturned crown, blood unfurling from its jaw like a movie carpet.

“Ma,” I said, sitting behind her, “you will get sick.”

“My whole body aches,” she said.

“It’s not safe to walk around so late.”

She snorted. “I walked around later in Jackson Heights.”

“I’ll make us something at home.”

She grabbed at her knees. “You’re not listening. He’s gone. He didn’t like us.”

“You have to forget some things.”

She whirled about as if I’d hit the deer. “When you’re gone, who’ll I have? In all your time at the restaurant, did you plan for that?”

It is true. Small-boned like birds, slim-numbered so even Indians ask, Assam where, a duo that, minus one, wouldn’t be a family at all. True too: sooner or later, I will be another man down. Each night Jumi flicks on movies, I riffle through X-rays for a heart larger than even I’ve tried to make it. Pulpy, oval, dripping—the fruit I’ve eaten lodged inside. “Wear and tear will catch you,” the doctor says. “Leakage will make the pressure drop.” I nod but know, all fruit ripens, then bursts. When mine does, I will offer Jumi every sour piece. You may not like this but I promise it is yours.

Though I said nothing, just stared at the still-still maples, waiting for dawn to rustle up their flutter, the deer. When the light did spill over the asphalt, the shuddering leaves swept dust at the coming cars. The deer blazed: every ruby clotted between every hair, those glazed eyes that stayed on us. As if we were the full-grown road kill. I winged Jumi up then in my left arm, the way I had when she’d been a pigtailed girl who’d burst out leaden school doors and hidden her face in my onion-scented shirt. Except she trembled now, so hard that, for several blocks, I thought she’d seize. Only at the base of her stairs did I notice my soaked sleeve and, as I hoisted her step-by-step, I said, “Think of the past as a dream. Now you’ve awoken.”

She jerked away—“I don’t want your useless advice”—and flung off her clogs, stumbled to the cot. Several minutes later, she snored toward the wall.

From then on, I drove between the studio and the restaurant, turning onto Bronx River Parkway only for meds or mail. Our avenue would be stickered with leaves the wind had rustled off oaks and the damp stoops would be sweet with musk. The house, strewn with clothes and teacups, was a mausoleum, where all I wanted was to corpse under a comfo

rter. Instead, I stared at my tiny outline in the hanging lamp and wondered, how could anyone wander on stars alone?

Last night, I found her sobbing before a display of wedding necklaces, which shimmered in the frosted Shop-A-Lot. I lay my hand on her braid but she pounded her fists on the sidewalk. “Get away from me!” Then she leapt up and marched across the pavement, past the Indian grocery, the Korean laundry, the shops adorned with silent brass gods. Each time she reached the L-end curb, she trekked through the lot of floating receipts and sobbed in Assamese. How she was stuck in this crummy life, how she hated being from a nothing family, how could he have said what he said after everything.

“Jumi! Listen!” I called as we hiked into wind that sliced our cheeks and tossed my cries to the ice rink fields. But round she marched and muttered, so I followed her until the night’s dots petered out into a warm pink sky, cars slowed to honk, and I slumped. Knee-sore before the jewel display, I shook—Jumi turned—I wept—her pupils thinned into a cat’s. Thing was, a hundred times I’d tracked her and a hundred more times I’d go, but she wouldn’t answer to her name. What I’d chosen for her in the hallway where the doctor had said, “Mr. Saikia, we couldn’t save your wife.” Still, I’d written a good name on the clipboard and whispered a second, my mother’s, into her ear for luck.

“You’re cold.” Jumi rested her hand on my scalp.

“I’m tired.” I didn’t mention the doctor’s visit.

With a hoarse laugh, she hauled me up. We walked arms linked, down Oaktree Road, its flatland sides sheathed with snow and light.

Jumi spoke: the first time Walt had visited Jackson Heights, he’d suggested they play a game. They would tell the shop ladies they were marrying. They moved from spot to spot, Jumi slipping on the heaviest sets studded with rubies and emeralds, Walt assessing each nose ring, bangle, jhumka. Always, the ladies cooed over what a pretty couple they made, asked for the shaadi details.

“It’s amazing how easily he lied,” Jumi said. “How elaborate the stories got.”

A Delhi extravaganza with painted elephants; a pier reception of Boston’s finest families; a train-hopping honeymoon through Europe’s museums.

“I would’ve held it here,” she said. “I would’ve picked India, where he’d never been.”

The streets hummed with men speeding in their sedans, with secretaries stanced on corners for buses. I wanted to say something about timing—about luck as we climbed her slippery stairs—but Jumi spoke about the theater. How long a leave she’d been given, which dancers had taken her place, who leapt in brittle bodies with the ferocity of wolves. She spoke like it was an ordinary day in these lawn-mowed parts where neighbors smile while taking one step back. Slept like it was an ordinary night, soundly, while I splashed my face, slicked down my thin side hair.

For sleep or no sleep, there is still Bollywood House. If there’s one thing I know, it’s that life can pink-slip you on any count: wife, country, job. Why, nights Jumi sleeps, I spread my arms to the patient moon. Come to us, I whisper to my memories. Come home.

STAR ONE

Mostly, Jumi, I see Pita buckling on his knees. In red muck we’d furrowed, me tightroping behind him, thumbing seeds into his careful holes. The afternoon your aunts called about the heart attack, I shut myself in the freezer, between the chicken and lamb limbs. Still, Pita’s eagle face flooded up, how he’d lain nose-deep in soil, too stiff to turn for air. That was precious dirt for you, sparkling jags Pita once rubbed between his forefingers. Nothing will ever smell as sweet. I was only sixteen then—ready to run from that mudhole—and thought, So romantic, Pita. So wrong.

Two days later, who but a lost son bumped in a rickshaw back into the gao? The road as unnerving as ever: green pools along its gravel edges, rippling rice khetis that, with the first rain, would suck these huts up. Women crowded every door, saris drawn across angular faces so that the blackest eyes bore holes into my back. Men turned from their tea-slurping in shops, rooster-clucking against scooters to stare, then spit. Children, as bare-and-loose-limbed as I’d been, scrambled beside the driver. Bidekhi ahise! Bhupen Mama ahise! As if I were a fallen god, a stranger even. I slipped into their chapped hands, the singsong of my sister’s cries from the threshold, even the choppy runs of the cows and birds that flew straight at you before swerving away.

Pita lay in the drawing room, blanketed with rose-and-marigold garlands, like some official. They had dressed him in the silk shirt and dhoti he’d worn three years before, when he’d sat on the bed and rested a shaky hand on my wedding headdress. Don’t be long, Bhupen. I kissed his cold toes, his swollen hands—two days dammed inside—and stroked his sunken cheeks. How could I tell him now? I would’ve called but the village has no phone; I would’ve written but you couldn’t read; I would’ve come sooner but the restaurant ate all the money. Too late-too late a bulbul shrieked from the roof. Women wailed in the next room, men smoked under the tamul trees, and children peered through the window bars, giggling.

Pita, the village storyteller who’d gathered them round our courtyard fire to recite Ramayana tales, lay mute under his ruffled cover.

“He called for you,” my sisters said over rice and khar, though they didn’t ask why I hadn’t come. Just Ba, chewing paan in the corner, said, “America must feel like heaven compared to this.” It felt far, though every aerogramme that landed on our Bronx table seemed like another ticking bomb. Always, they were naming the dead. A cousin who’d pummeled drunk into another truck, a nephew snipered by a paddycat who’d once been his comrade, a niece, married to a kaaniya eater, who’d hung herself in the bedroom. “A man must look out for himself,” I told my sisters over the phone and yet, again and again, I was yanked.

Back in Jackson Heights, I’d wheel my cart into some crowded aisle and find starfruit sitting like some far-flung relative between the mango and papaya. My heart would tremor before faces surged through me: Mai frying stars over the clay hearth, pushing salted bits at me in a silver bowl; Pita pruning kordoi branches, sun mottling him into a dark cheetah the Brits had long hunted out; my cousin cycling me atop his ramp, his basket of stars beckoning, every tangy orb the taste of those luminescent fields where we’d batted; and Tara, arm twining about her stick that first night, its top burning like the sun, all that inexplicable Oxomiya heat.

I couldn’t imagine, four years later, I’d be laying Tara atop blazing sticks. That the stench of her meat, marrow, oil would sting my nostrils. That her brothers, lined five-strong along the Brahmaputra, would pour her dust into the rushing waters. The sun, which swells into a dripping wound there, lit every fisherman, recruit, and junkie shooting for something. As if we all burned with need. Later, crouched about a fire they’d built before a beach dhaba, her brothers passed around a black-and-white photograph of her last wedding minutes. Tara stood, a waif thronged by these tall, bearded men, under a canopy speckled with moths and lanterns. Brightest of all were their pale faces, stern Ahom brows over steepled Ahom eyes, questioning the camera. As if America were a bug stuck in their throats. Though her brothers learned to speak it that last evening, asking me to leave America, to bring you, Jumi, home.

I couldn’t trouble them, there was no work, you were too young. What I meant was home was too exacting: asking for both eyes when you wanted to be seen, for your heart when you put forth your rice bowl. Why I rise every unexpected night, in this picture-perfect hell-freeze, tracking what’s left to me. Why I’ll follow stars round corners for a hundred years, rather than land before that watery snake, murmuring grace for another theft. Look at us: Ahom and Koch, we who were once kings, swatted like flies, yoked like mules. We who no longer recall ourselves. Tribal? Non-tribal? Other Backward Caste? No one in America makes heads or tails of this junk, so long as your wallet speaks. But home will spear you to the ground, so that you’re another Cat-Eye left to rot.

But the clearest reason, Jumi, is because you were born all me: sun-dark skin, fire-engine fury. Why I snapped a hundred pictures of you

, mailed them to the village, wrote in Assamese: our blood. Even then, we knew: only ragged faces and half-stories left to trade over fire, and the ULFA blackouts, the state machinery had dimmed those too. Why, when you screamed, a baby unchoked by Tara’s blood, I’d phoned the men.

“She lives! In America!”

“Tara?” they said.

And though the old name sanded into my gut, I wrote the new one on the hospital paper.

“Prarthana,” I said. “Prayer.”

Boiled Kordoi, Mashed

3carambola

1saucepan hot water

1tablespoon mustard oil

1teaspoon salt

1.Heat water to a boil.

2.Add unskinned carambola. Leave until gold color turns green and skin may be peeled with fingernail.

3.Drain and rinse carambola in cold water, then dry with napkin.

4.Mash with spoon or hand to pulp.

5.Add oil and salt. Should be spicy but easy to swallow.

BHUPEN

This afternoon, she begins early, locking herself in the bathroom, banging her head against the bathtub rim.

When I ask her to let me in, to just try me, she says, “Stop acting like you know! You didn’t grow up here. You never even dated.”

My hand slips off the knob. “Maybe you’re right. I don’t know a lot of things. But your uncles think you’re beautiful. You are a star in my heart.”

She sobs low to the ground, more fiercely, waves broken by hiccups. Several minutes later, I kneel and say, “Ma, please open.”

Her cries trickle to sniffles and she says, “I don’t want anyone to see me.”

“Seeing you like this,” I say, “is not good for me either.”

The door opens to her bowed head, hair tufting up like a nest. I kiss her forehead and her hot arms circle my waist.

Sugar, Smoke, Song

Sugar, Smoke, Song