- Home

- Reema Rajbanshi

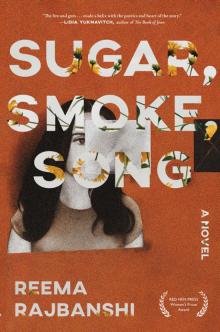

Sugar, Smoke, Song

Sugar, Smoke, Song Read online

SUGAR, SMOKE, SONG

SUGAR, SMOKE,

SONG

a novel

Reema Rajbanshi

Red Hen Press | Pasadena, CA

Sugar, Smoke, Song

Copyright © 2020 by Reema Rajbanshi

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the prior written permission of both the publisher and the copyright owner.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rajbanshi, Reema, 1981– author.

Title: Sugar, smoke, song : a novel / Reema Rajbanshi.

Description: Pasadena : Red Hen Press, [2020]

Identifiers: LCCN 2019049314 (print) | LCCN 2019049315 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597098915 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781597098908 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Young women—Fiction. | Asian American women—Fiction. | Experimental fiction, American.

Classification: LCC PS3618.A4335 .S84 2020 (print) | LCC PS3618.A4335 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019049314

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019049315

The National Endowment for the Arts, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, the Ahmanson Foundation, the Dwight Stuart Youth Fund, the Max Factor Family Foundation, the Pasadena Tournament of Roses Foundation, the Pasadena Arts & Culture Commission and the City of Pasadena Cultural Affairs Division, the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, the Audrey & Sydney Irmas Charitable Foundation, the Kinder Morgan Foundation, the Meta & George Rosenberg Foundation, the Albert and Elaine Borchard Foundation, the Adams Family Foundation, the Riordan Foundation, Amazon Literary Partnership, and the Mara W. Breech Foundation partially support Red Hen Press.

First Edition

Published by Red Hen Press

www.redhen.org

Acknowledgments

So many well-wishers crossed my path as this manuscript took shape over eight-plus years.

Brave writers taught me literature was serious business: Patricia Powell, Pam Houston, Lucy Corin, Riché Richardson, Chris Abani, Elmaz Abinader, and Anna Joy Springer. Thank you for believing I had something to say.

California friends became the family this book needed: Alan and Alicia Brown, Antoinette Rose Mendieta, Carolyn Menard, Michael Robinson, Moazzam Sheikh, Pranami Mazumdar, Seeta and Sambhu, Tsomo and Samten, Maché, Bascom, Chloe, and Brian. Your love and jokes saw me through the harder years.

To friends and family in New York City, Northeast India, and Brazil: thank you for sharing the lessons of your struggles and the ferocity of your art over hearty momos and drinks!

To all those who read drafts of these stories or who published them, especially the clear-sightedness of Kate Gale and her hardworking team at Red Hen Press: thank you for the essential magic of building a reading community.

And to my parents and grandparents: thank you for passing on the indelible value of literacy and how, for some of our dreams, it is never, ever too late.

Deuta (Bimal Rajbanshi), for the gifts of faith and revision.

Contents

The Ruins

BX Blues: A Dance Manual for Heartbreak

Ode on an Asian Dog

Swan Lake Tango

The Stars of Bollywood House

The Carnival

Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughter

Sugar, Smoke, Song

One Tiny Thing

SUGAR, SMOKE, SONG

The Ruins

My sister’s left me to the night. Its mouth of stars, this glass between them and me, this bed where I lie in half. She’s left me for that half-breed sister, Assam, arms she’d thrust in mine spread for jungle, legs she’d wrapped me with run for hills. To the ruins hidden there, carved with stories wearing off with rain.

All I’ve got are mute stars in a black Bronx sky, and no sister to name the fiercest bits. “Scorpion, the Hunter, the Bear,” she’d say, pressing her finger to the glass. “And Gemini. Twins like us. Split personalities.” But no twin tonight, palm on navel, lip on shoulder, to rein me in with what else she’d seen. “Maina, the crazy on our corner tried talking to me. Took off his cap, started tap dancing. Maina, did you know mice pee when they die? I saw it in the lab. Dr. Klein had me etherize fourteen.”

So I take what’s left, my sister's most private thing. In a blue book shelved behind the others, Biju recorded her life in even cursive: the eggs, the clouds, the rattling number five, how well the slides of brain tissue magnified one evening. I rip her pages and spread them on the floor—I know I should be last of all to take my sister’s words—but rules have never stopped me.

She’s crammed the lines, scribbled the letters as if worried someone might read her. And archaeologist that I hope to be, I will decode her script. Here she kept her one true language, while all the rest was ruse, silence snaking a tomb.

Mom knocks in and too late, I shield the page, ’cause up I glance at my sister’s wary eyes, hear the pause that won’t prod me when there’s nothing I want to confess. Only when mom shuffles out do I smooth that first yellowed page and think: my sister was good, she was smart, she was better than me.

June 18, 2003

A week since he came at me. I couldn’t even tell what for. Not then, not now. All I saw was his face. Pasty white with shot, rolling eyes. The knife swirling at me like he was hacking through brush. Everyone keeps asking, How’d it feel? Fire. Like pricks of fire zipping ’cross my face. And the blood. It didn’t spill like in the movies, just welled up in lines, like I had a hundred paper cuts. Down my nose, round my mouth, on my lids, my vessels sliced on both cheeks. I didn’t scream either. Just froze, like I was stuck in a block of ice and here was this master artist come to carve me out. Bring me out to life.

He muttered when he walked away. I think I slid, on one of those subway columns. Our train was whizzing by. Angry, clanging, rushing east. Maina was running, too frantic to make a sound, going west for anybody. Through all those people who didn’t do nothing. Just stood there like it was a show and everybody was supposed to be polite and watch. When she knocked on the ticket booth glass, the MTA guy raised a palm. “Honey,” he said. “You see the line. Get on the back of it.”

Thank God the doors opened when they did. The conductor shouted for the cops. Maina was holding me. She was trembling. “Wake up,” she said. “Don’t die.” I wanted to tell her, It’s fine. He didn’t get my heart or my guts or my kidney. Just my face. I’m still alive.

But white blots were blooming all over. Mouths were opening and the sound was off. Stars bursting up-close. I could hear my breath, going so fast it was like that was what kept my heart pumping.

Biju forgot some things and lied about others. She forgot to say how the cops caught the guy, who’d loped away like a giraffe, swinging his long limbs, the knife slick and bright in his blue-veined hands. His glide was amazing, really, like some slow-motion shot in a black-and-white film, where everyone’s frozen except the villain and the victim, and the only color is red, that one streak on the villain’s knife, which grows smaller, and the rivulets seeping into the victim’s shirt, then her sister’s jeans.

’Cause there I was, kneeling on the platform, holding Biju’s face between my hands, trying to stopper the blood that was dribbling like tomato juice from a broken bottle. There he went, ambling easily along the platform, veering into the crowd that parted like he was Moses or something. A Dominican man with the inflated chest of a superhero sprinted and jumped the guy, threw him down on the platform’s broad yellow stripe, then pinned his scrawny arms back.

Biju lied about what she said as she lay in my lap. She didn’t say she’d be fine. She was crying, her wor

ds garbled, the blood bubbling from her lips. She shut her slanted eyes, the only tribal trait I could find in the marred rises of her face, and asked, “Maina, what’s happening?” I was the one who felt I’d vomit on my sister’s shambles. I was the one who said, for her and for myself, “Shh, just breathe, stay awake.”

Biju didn’t write about the hospital, though every time the ambulance jerked, she’d turn her face to check on me. The medics had covered her with rolled washcloths to soak up the blood, but still, they set the mask unclipped, so its edges wouldn’t bite her cheeks. With every breath, that mask fogged and cleared, showing her tender lizard tongue curled under her red-stained teeth.

For thirty minutes, I paced the hall alone, until nurses wheeled Biju into the ICU. In filed our procession, Mom, Dad, and friends circling her shrouded body, pliant plastic tube forcing itself out her mouth, nervous green line on the heart monitor beeping and jumping. The women stared and the men fidgeted, while someone led Dad out through the curtains. They wouldn’t let me follow, but still I could hear him, we all could. It was like nothing I’d ever heard from a man, a noise bursting out in fits, so fierce it filled our room, must’ve rung in the hall where he sat, an animal sound that demanded privacy and listening.

July 15, 2003

Dr. Perry fixed my face, though I haven’t seen his yet, just felt his hand smoothing out my brow when they laid me down this morning. If Maina were here, she’d say, That’s okay, hands tell you everything. She wouldn’t talk about The Thing, his sickly arms, the veins bulging like they were gonna burst, the knife his fingers gripped.

After the attack, she’d point out hands to me on the train. “Look,” she’d say. “The old man in his bowler hat, paper covering his face: a thinking man, sharp knuckles, spare fingers. Or here, the guy in his paint-splattered duds, slumped against the silvery wall: brutish hands, rough skin, but see the palms slip off the knee, soft and scarred inside like Dad’s. Or there and there,” the hands of men who’d look Maina up and down, wouldn’t flinch when she cold-stared them back: mottled hands, lotioned fingers sliding up and down the poles.

I’d tell her, “No, I believe in faces.” All those train rides, all I’d notice were eyes darting away, glancing again, dropping to the floor. Kids pinched their cheeks this way and that, even the adults stared and whispered. In the glass behind them, I’d catch my scars, red like wires mashed into my face.

But I’ve got no sister to tell now, gone tramping through jungle for clues to our past. “Good luck,” I’d whispered our last night in bed, but I want her here, below this sky I’ve named, its face shielding hers and mine.

I should be grateful to have a sister so fearless, so pretty. That’s how I got my surgery for free. Dr. Perry is Josh’s dad; Josh is the Jewish boy who told Maina he’d do anything for her, even wipe my scars down to almost nothing. “Almost,” I said to Maina my first night back, and had her finger the pink ridges. “If you look hard enough, the marks are still there.” Then Maina whispered back to me: she only kept him around for my sake. When she shivered into my arms, I warmed her cheeks with mine, but wondered if her soft bedtime eyes were real, or if she always grabbed what she needed, then up and left for something better.

Biju was right about the taking. After the slashing, I couldn’t seem to stop. First there was the gauze, rolls and rolls I grabbed from the drawer by her hospital bed. Then there was the stuff rich girls get easy—foundation, cocoa butter, cream—which I swiped from stores, anything she and I might need. A month later, flying into Assam, I was taking everything.

On the Mumbai plane, I rummaged through the purse of the woman sleeping next to me, saved the batteries I thought might come in handy, an address book for when I’d have to call somebody. In the terminal to Guwahati, I grabbed sandwiches from the counter, handed them to urchins wandering barefoot on the shiny airport floor. I couldn’t stand to see them, so young and sullied, calling out with wants people were ignoring. By the week I trekked for those ruins, I had a practiced hand, and whatever I fancied, palace stone or temple carving, any fractured thing, I took.

Though the stone I wanted most, I couldn’t move. Narasingha, mane loose, tongue out, in the middle of rubble that was Ukha’s palace. Even rain, which hits this earth harder than any other, wearing the rock-carved gods off their chariots, couldn’t topple that image: God come to save a boy. He was a prince, who wouldn’t pray to the king, so the king decided to kill his son. The man was crazed with himself and made so by the gods, who’d promised him no death, day or night, on earth or sky, by animal or man. And yet God heard and came at dusk, a lion’s head on a man’s body, and lay the king on his lap and ripped him wide with his claws.

Running my hands over that cold carving was like touching the new contours of my sister’s face. How was she caught on this hill, in Ukha’s house? Centuries before the British and Tai-Ahom named us Assamese, a tribal king had set magic stones to guard his daughter. On top, he posted his sentinels to watch her sleep, and on bottom, lit a circle of fire so no man could touch her. Still his kingdom crumbled—only the hill survived.

When I returned to the Bronx, my sister had stopped talking. Biju would not leave the bed till noon, would not walk out onto the pulsing streets where men will not let a pretty girl go without a comment and a damaged girl pass without a laugh. She would not breathe a sound as she ate rice or watched TV or roamed the house like a phantom—what I could have been. Nothing could shake her out, not my photos of the hill people, not the Himalayan jewelry I’d haggled over, not the birthday fiesta Mom and Dad threw to warm her with friends, make life look normal, celebrate what we hoped was a new beginning.

August 30, 2003

Big party in the basement for our sweet sixteen. Sweet, I suppose, ’cause I’m alive, my face intact, scars partly gone, Maina back on Bronxwood Avenue. Though I can’t help hating whatever the hell did this to me and not to her. We were alike as two people split from an egg can be until The Thing came up—slice!—life cut me and Maina in half again.

Mom says it would’ve happened sooner or later; Dad says we were always different, that no matter what, I’m a beautiful girl, someone will come who sees my exact beauty. Though I can’t buy lines like that anymore. What I hear are people saying around the table of White Castle burgers, to Mom and Dad, We were so sorry to learn, or to me, Mami, you look so much better, or to Maina, Wow, this one’ll make the boys go mad.

Maina hears it all and pulls me upstairs to our bedroom, where we find ourselves before the mirror. Like looking at a before and after shot, or split halves of the god-and-goddess pair, Shiva-Kali. Maina, the regal mountain god, loinclothed in animal print, and me, his blue and angry wife with her bleeding tongue. We stare at what remains the same, heart-shaped faces, Mom’s buttercream coloring, her slender Aryan frame, the tribal eyes we got from Dad, his straight hair, the sideways glance we give everybody but each other.

It’s Maina who turns away, who cannot face the contrast. She rummages in the drawer for a scent, telling me how she stole the bottle, how it smells like jasmine, the flower that grew thick in Assam. “The ruins,” she says, “Biju, they were amazing. Man, those ruins are us, they’re our history.” In the mirror, my eyes eclipse, and I find in them all the things Maina describes: fish flashing silver through the river, shadows cast by bamboo fronds, embers of wood coal as they glow, then fade. My face swells in the mirror, slashed over and over like the corpses piling in the jungles of Assam, lines the British drew on hills and plains they took from the Burmese, all the ways Indians watch tribal faces but turn from them too. My fine, mutilated face looms in the mirror, and I think, I am my history, I am my history, I am my history.

After that summer, Biju and I no longer sat in the same classes, never teamed up on handball. The autumn horde pushed us down opposite aisles, Biju to bio, me to archaeology. So that late into evening, I’d compile photos of ruins in an abandoned room while Biju stood outside on the sidelines of the court. The girls huddled without her, the

boys rattled the chain-link, chanting Barface B. My sister crossed the street, then bussed to lab where she’d wash brain tissue for hours, read the paper front to back.

Even at lunch, when boys eyeing our derrieres, which must’ve looked exactly the same, sat at our table, an execution light turned on. They couldn’t help it—they’d look and speak to me. They wouldn’t give my sister another glance, pretend to be polite, remember there was a body identical to mine sitting between us. I tried once to rise, but Biju held my elbow down. “I don’t blame them and I don’t blame you.”

So I dated one and another and another. I wrote a list of penances I was paying:

Thanksgiving: Jacob Stein, lanky, Jewish, sixteen. Pedantic, cocky, snorted when he laughed. Never topped three minutes.

Christmas: Drake Lloyd, articulate, black, eighteen. Smart, slacker, sexy. Best phone technique around. Bedside manner lousy.

February: Ravi Gupta, hairy Gujrati monkey, eighteen. Cheated three times. Smallest dick in high school history.

March: Ray Soto, slender, Puerto Rican, sixteen. Gentle, sweet, boring.

April: Tommy Storelli, Riverdale boy, Godfather speak, seventeen. Rich, crazy, druggie.

On and on, in dark cramped rooms, the stalls of public baths, the benches of parks, and yet the boys, their sweat, their stupid fumbling ways were all the same. As they nuzzled their noses in my neck or wound down my torso with their lips, they’d murmur, “Man, you’re fine.” It was then, no matter where I lay, whatever ceiling or sky I saw, I would hate them, know that whatever it was they liked, they couldn’t really see me. Always in the night, I would ask, “Do you think my sister’s pretty?” The dumb ones yawned, “Nah, you guys look so different, we would never mix you up.” The sly ones answered, “Sure, yeah, your sister’s sweet.”

Sugar, Smoke, Song

Sugar, Smoke, Song